Machine learning for records management

Automated records management

NARA seeks industry help to automate records management

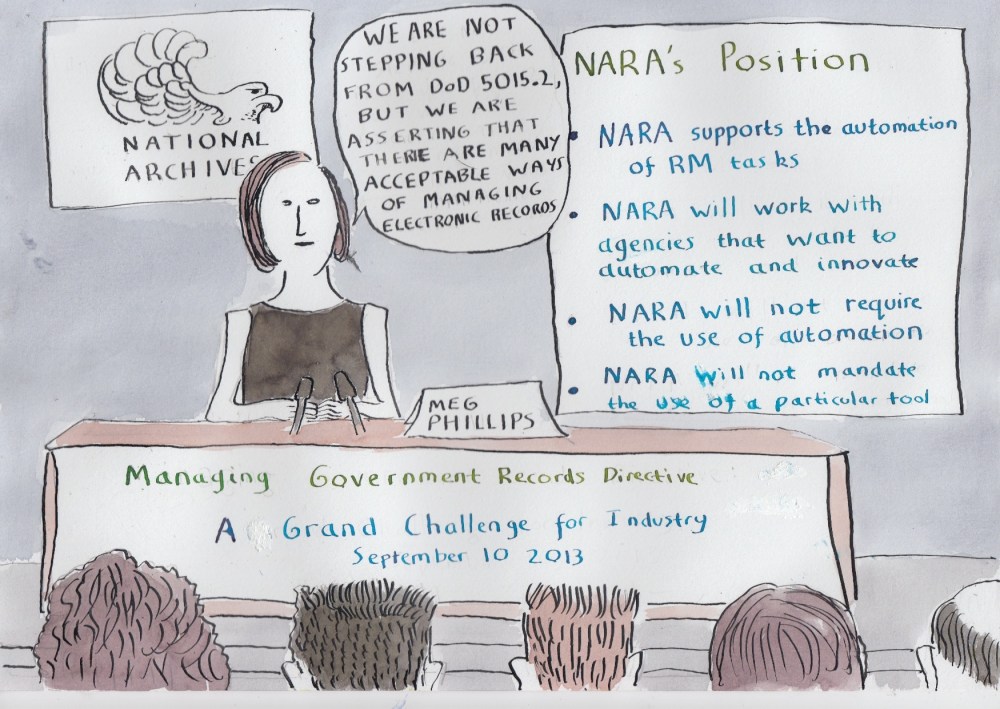

On the morning of Tuesday September 10 the US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) hosted an event at which the vendor community were able to listen to NARA explain their core attitudes and beliefs about automation and records management. NARA used the morning to invite vendors to submit information about their existing products, as well as ideas and suggestions for viable automated solutions.

Meg Phillips is External Affairs Liaison at the US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) and she gave an introductory speech setting the goals and context for the event.

Here are the main points I noted from the speech:

- Many federal agencies are still using ‘paper-inspired’ records management processes.

The bigger agencies are finding such processes hard to scale

- Federal agencies have relied heavily on electronic records management applications certified against standard DoD 5015.2. NARA still believes that this is a viable approach.

However the problem is that the penetration of these systems is not very deep. Even when agencies have implemented such electronic records management systems, there are still considerable quantities of information that are falling outside the scope of the electronic records management systems and that are going unmanaged

- NARA believes that with types of electronic records such as e-mail and social media there may be other ways of managing them that will work just as well or better than the electronic records management system approach

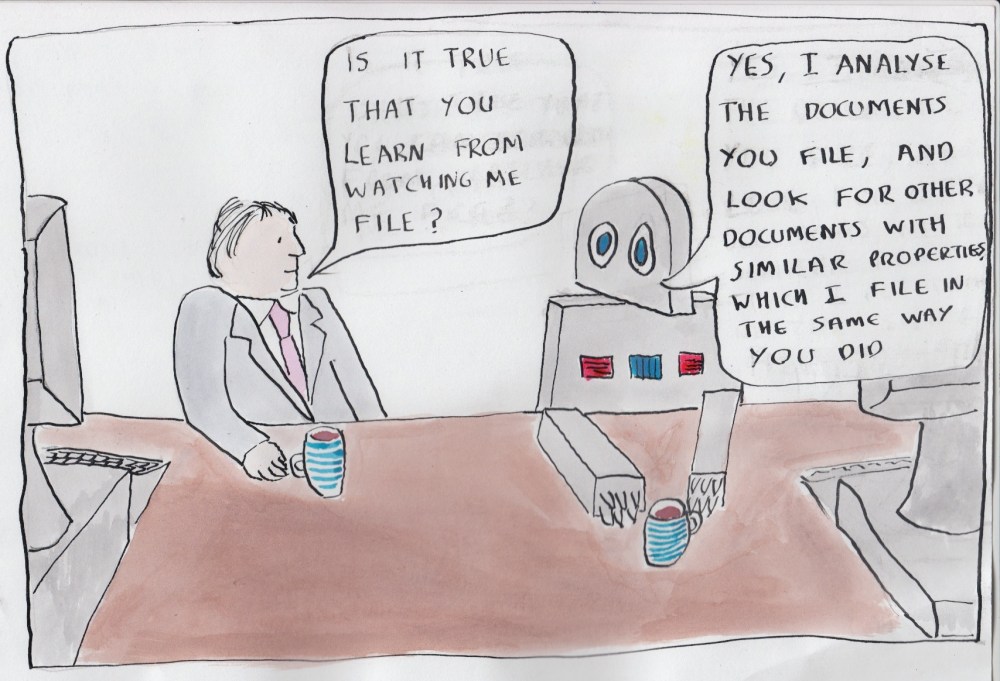

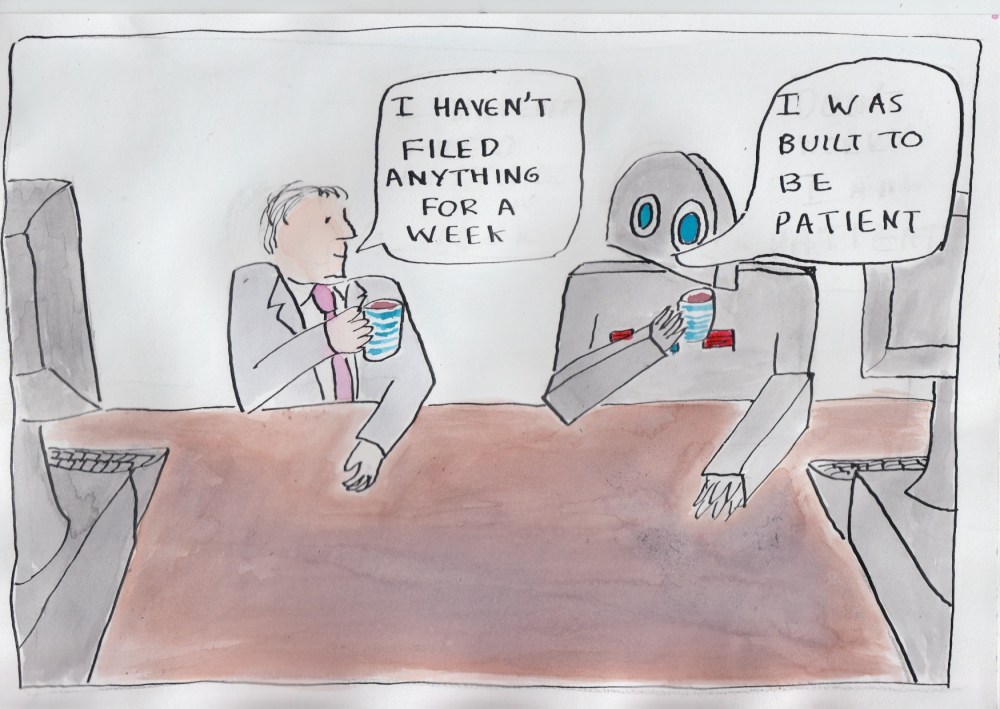

- NARA is working on the assumption that automation can improve the consistency of records management outcomes, and reduce the burden on end users

- NARA are looking to ‘change the conversation’ about records management. In particular they are looking for more consistent and more compliant record keeping in federal agencies

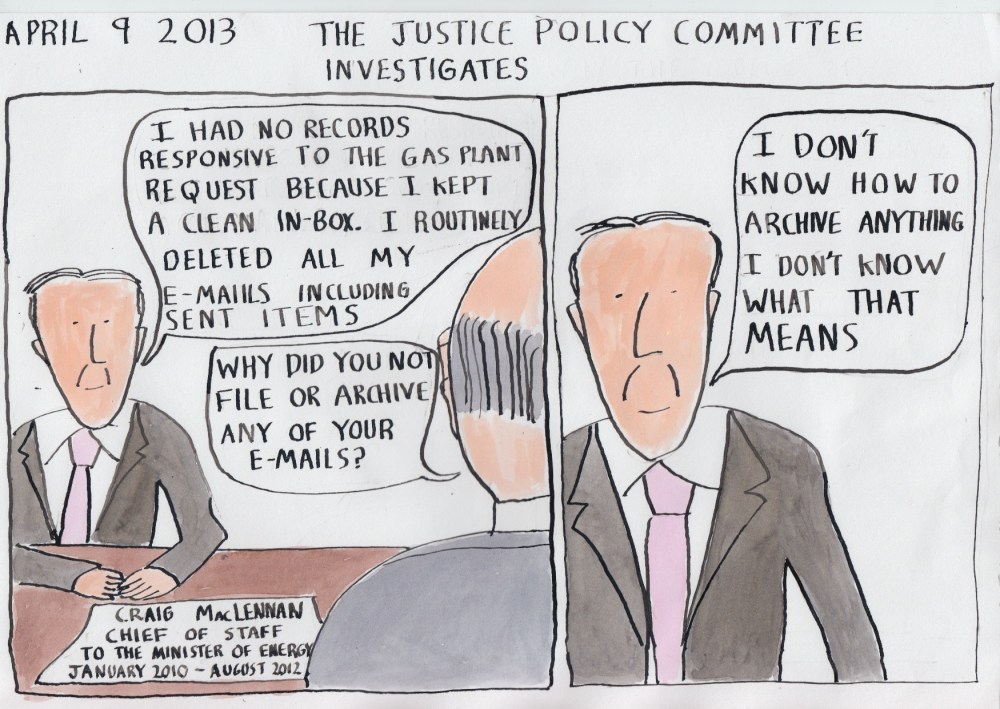

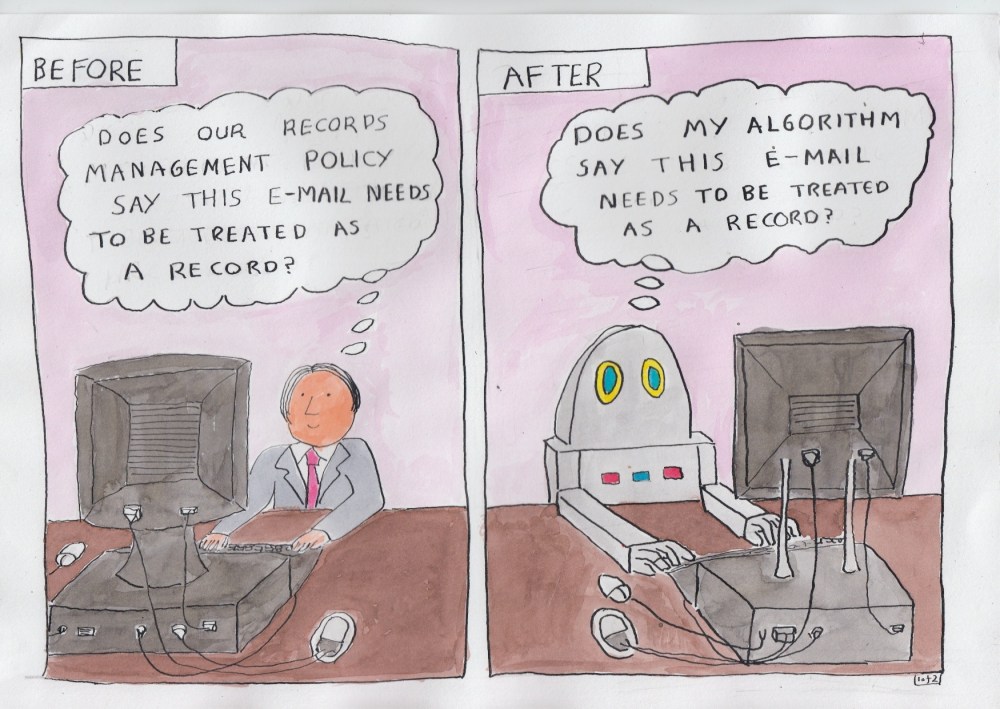

- NARA believes that the consistency and compliance of record keeping is directly linked to the burden on end users. If an Agency imposes a significant burden on busy staff by asking them to make decisions on every individual e-mail that they receive (should it be treated as a record? if it does need to be treated as a record how should it be filed/categorised?) then this is likely to have a negative impact on consistency and compliance

- NARA believes that automating records management decisions to the maximum extent possible will lead to greater consistency and compliance, will result in better records, and more accessible records

- NARA are looking for solutions that will both scale up to the needs of big agencies but would also scale down and be affordable for smaller agencies with small IT budgets

- NARA will start by establishing the state of the market in terms of what products are already out there for automating records management processes.

This would enable NARA both to increase awareness within federal government of what is already available, and to identify any market needs that need to be addressed

- NARA wants to identify solutions that can automate records management processes, including auto-classification, and innovative approaches coming out of the e-discovery vendor community

- NARA does not assume that open source is the only way to go, but it is one avenue that they need to explore

- NARA actively supports the automation of RM tasks. They believe this may be the only truly scaleable way to consistently and compliantly manage electronic records in high volume environments

- NARA believes this is a sea-change. They will actively support agencies who are willing to innovate and try approaches that are not yet tried and tested

- There will be no obligation on Agencies to introduce automated records management processes

- As well as reducing the records management burden on individuals, NARA are also looking to ease the passage of electronic records through their lifecycle, by looking at tackling ‘moments of risk’ in the life of records. One of these moments of risk is when records transit from one application to another. NARA wants to find ways of making the movement of records from one system to another less onerous and risky

- NARA are looking to standardise the way electronic records of permanent value are transferred to them from Federal Agencies. NARA has a digital repository, which accepts ‘submission information packages’ (the term used in the OAIS model for a new accession of records to the repository). NARA will draw up a standard for how such submission information packages should be put together

You can see a video recording of the whole speech on the NARA usenet site (Meg’s speech starts 13 minutes into video number 1).

Background to the event

NARA’s call to industry comes in the context of the ‘ Managing Government Records Directive‘

issued in August 2012, which sets two central goals to US Federal Government . One of the goals commits Federal Agencies to manage records in a manner consistent with Federal statutes and regulations and professional standards. The other goal states that:

- all e-mail must be managed electronically by 31 December 2016

- all permanently valuable electronic records must be managed electronically by end 2019

The goals themselves are neither particularly interesting nor at first sight, particularly demanding.

What is interesting is the manner in which NARA is committed to achieve it. The Directive commits NARA , among other things to:

- issue new advice on the management of e-mail (this prompted NARA’s Capstone advice that I blogged about recently)

- investigate the embedding of records management into commercial cloud services

- investigate the feasibility of establishing central cloud service for the management of unclassified cloud records

- investigate the possibilities for reducing the burden of records management on agencies through automation

- revise its guidance on the transfer of electronic records to the National Archives to ensure it stays current with technology trends.

NARA are committed to reporting by 31 December 2013, on the two commitments relating to the cloud, and the commitment relating to automation.

Sub-goal A3 of the directive commits NARA to ‘investigate and stimulate applied research in automated technologies to reduce the burden of records management responsibilities’. In particular it commits NARA to:

- work with private industry and other stakeholder to produce economically viable automated records management solutions

- produce, by December 31, 2013, a comprehensive plan to describe suitable approaches for the automated management of e-mail, social media and other types of digital records content

- obtain, by December 31 2014, external involvement for the development of open source records management solutions

Update:

NARA have published a blogpost about the event. Cheryl McKinnon attended the event and posted this blogpost

NARA’s grand challenge for industry

E-mail and succession planning

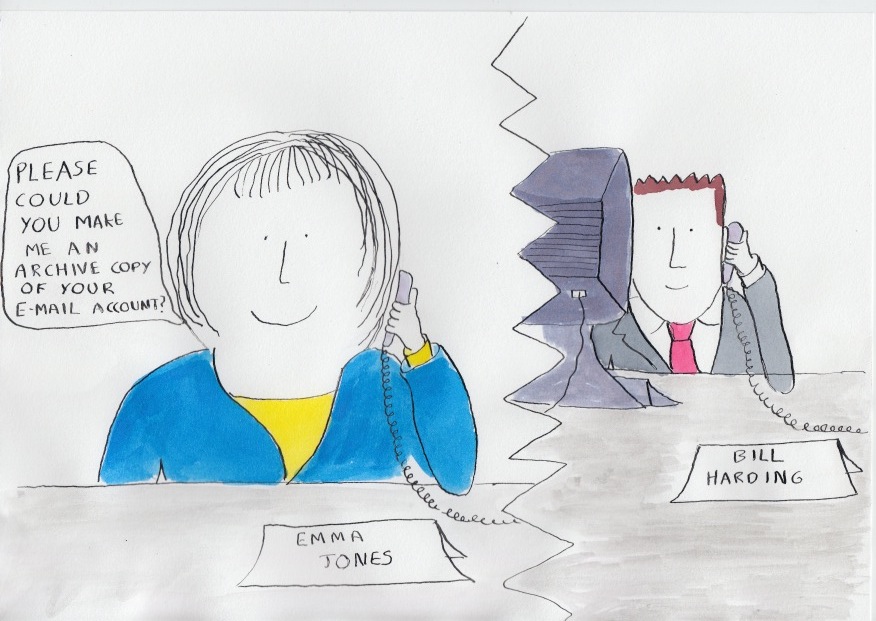

One of the core problems with standard e-mail accounts is that business communications accumulate in individual accounts in a way that ensures they are not routinely accessible even to close colleagues.

This was brought home to me when I worked with an organisation that had shared drives, a collaboration tool, and an electronic records system, but who conducted most of its business through e-mail. A key part of their work was influencing and managing relations with external stakeholders, and the communications with those external stakeholders were for the most part only captured in e-mail.

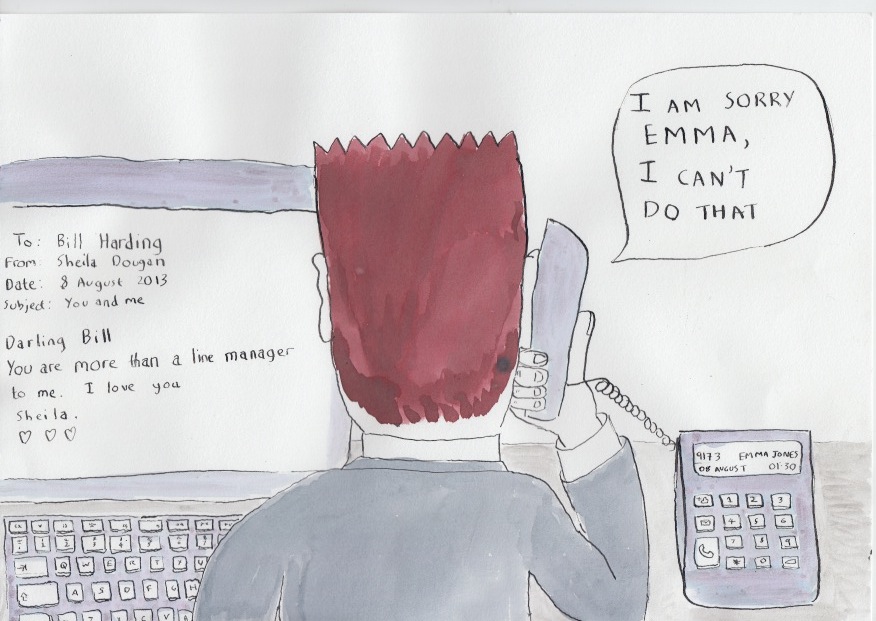

A practice arose that when an individual left to take up another post elsewhere in the organisation, then the internal person replacing them would ask that individual to make an archive ( .pst) file of their e-mail account. Sometimes the individual agreed, and left them a copy of their e-mails on the shared drive. Sometimes they said no.

The practice was not officially supported or condoned (though it was not outlawed either).

This is a succession planning issue. Staff starting a new role often need to see the e-mail of there predecessor, in order to carry on with the working relationships of there predecessor. One person told me that she had transferred roles several times, and she had found it significantly more difficult to get to grips with a role when her predecessor had not provided her with an an e-mail .pst archive.

There is an element of absurdity to the situation. There was no benefit to the organisation for e-mail to be duplicated to a flakey .pst file sitting precariously on a shared drive. The organisation already held all of each outgoing post-holder’s e-mails, it just had no way of letting their successors see them.

The presence of personal communications mixed in with business communications means there is no purely technical solution to this problem.

Why NARA has no option but to preserve significant e-mail accounts

On 30 May 2013 the US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) opened a consultation period on its proposed ‘Capstone’ approach to managing e-mail. If the approach is adopted US federal agencies will be asked to schedule the e-mail accounts of senior staff for eventual transfer to NARA and permanent preservation.

On 30 May 2013 the US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) opened a consultation period on its proposed ‘Capstone’ approach to managing e-mail. If the approach is adopted US federal agencies will be asked to schedule the e-mail accounts of senior staff for eventual transfer to NARA and permanent preservation.

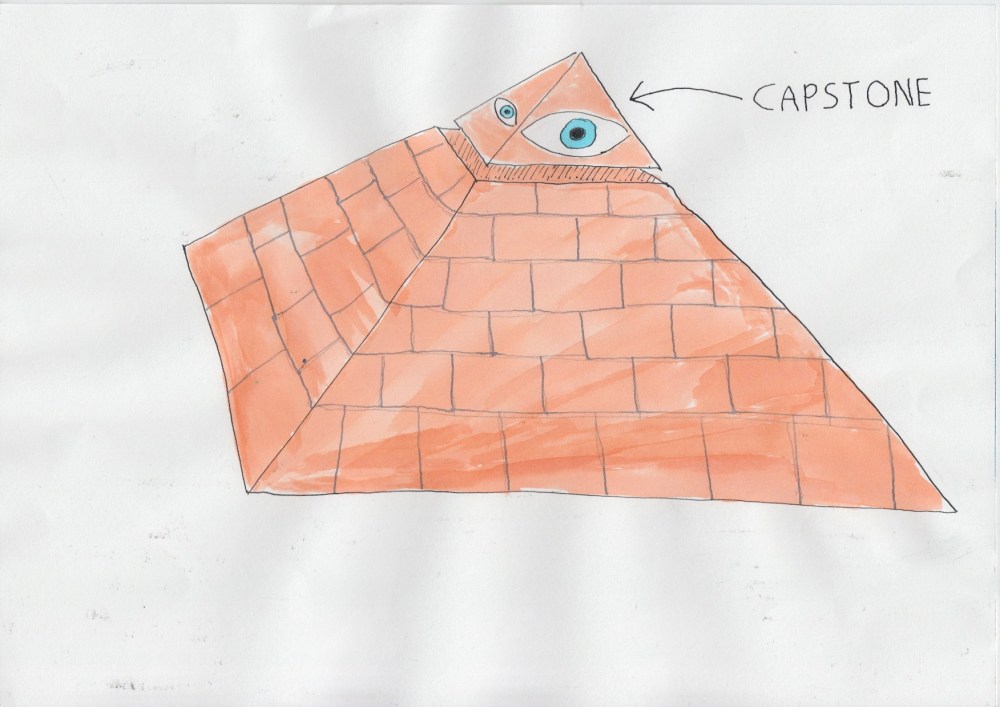

‘Capstone’ is the term used for the apex stone on top of a pyramid. The capstone is the only stone in a pyramid that looks out in all four directions. On the US dollar bill the capstone of a pyramid is depicted as an all-seeing eye.

NARA are hoping that the e-mail accounts of senior managers act like the capstone of a pyramid. They are working on the assumption that all major discussions and decisions in an organisation are filtered up through one or more members of senior management, and leave a trace in their e-mail accounts.

The nature of the Capstone approach to e-mail

Here is an extract from NARA’s description of their proposed Capstone approach:

Capstone offers agencies the option of using a more simplified and automated approach to

managing email, as opposed to using either:* print and file .. or

* records management applications that require staff to file email records individually.

Using this approach, an agency can categorize and schedule email based on the work and/or position of the email account owner.

The Capstone approach allows for the capture of records that should be preserved as permanent from the accounts of officials at or near the top of an agency or an organizational subcomponent.

An agency may designate email accounts of additional employees as Capstone when they are in positions that create or receive presumptively permanent email records.

Following this approach, an agency can schedule all of the email in Capstone accounts as permanent records.

The agency could then schedule the remaining email accounts, which are not captured as Capstone, as temporary and preserve all of them for a set period of time based on the agency’s needs

What does Capstone mean for electronic records management approaches?

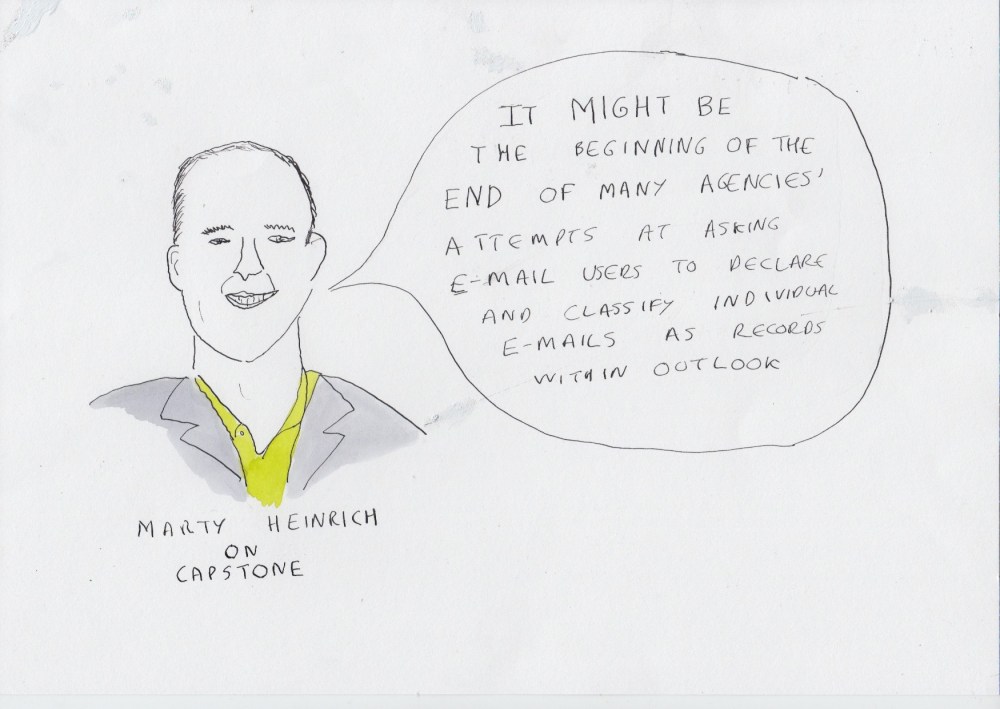

The quote in the picture is from Marty’s blogpost on Capstone

It is almost two decades since e-mail came into general office use in countries such as the US and the UK. For most of the this period central/federal government bodies in major economies operated an ‘electronic records management system’ approach. This involved implementing an electronic records management system (or rigging up a collaborative system such as SharePoint or Lotus Notes to act as one) and asking individuals to move documents or e-mails needed as records into that system.

Some such organisations tried to prevent staff ‘hoarding’ important e-mails in their accounts by either placing size limits on e-mail accounts, or automatically deleting e-mail from e-mail accounts after a defined time period (for example a year after receipt).

Such organisations would tell their staff that e-mail was a communications tool, not a recordkeeping tool, and that e-mail accounts were only a temporary storage space. They would tell staff that anything needed in the medium and longer term must be moved onto a file in the records system.

NARA’s proposed Capstone approach effectively turns this on its head. It asks US Federal agencies to treat e-mail accounts as records – records that will , for some key members of staff, be kept in perpetuity.

A senior member of staff who left all their e-mails in their e-mail account and never filed or deleted anything, would in theory, be meeting their accountability obligations to US citizens.

In practice Federal agencies are going to have to carry on asking staff to move (or copy) important e-mails out of their e-mail accounts, even after Capstone comes into implementation. Capstone is not a records management solution. For example it does not solve the problem of staff being unable to access important e-mails sent/received by their predecessor. This is because the accumulations of private communications in e-mail accounts make standard e-mail accounts unshareable.

Without e-mail accounts there will be a black hole in the records

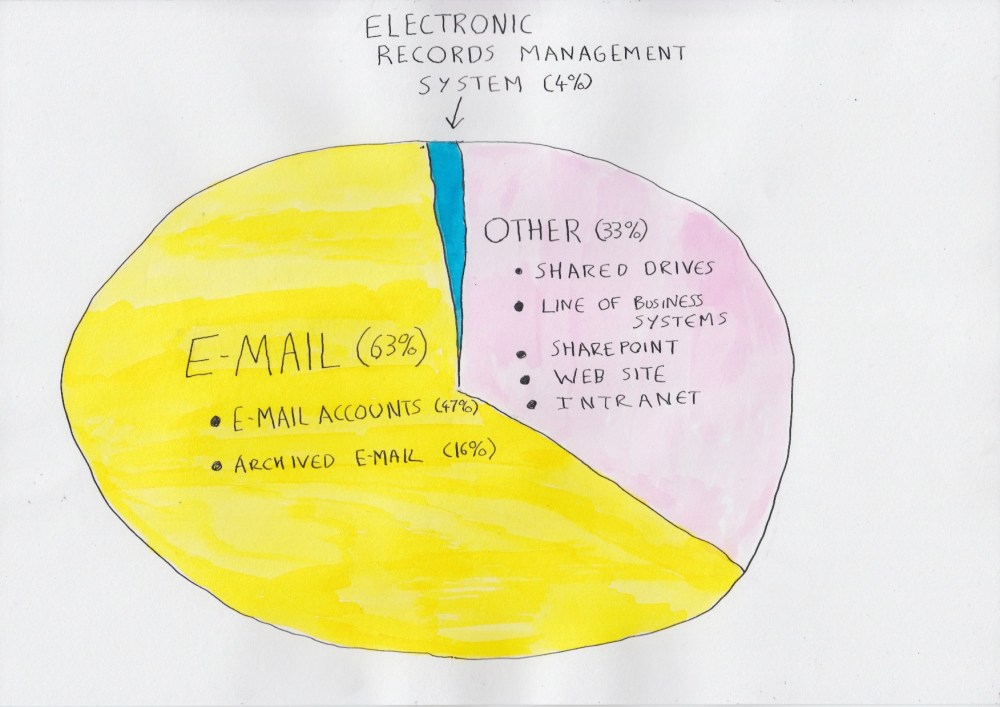

Storage percentages given to me by a global multilateral institution

To understand why NARA are proposing to permanently preserve e-mail accounts let us look at what happens when an organisation implements an electronic records management system.

I recently heard a talk from a global multilateral institution who had a strong records management programme in place. They had a good culture of record keeping stretching back over many years, longstanding senior management support, and a knowledgable and committed records and archives team.

They had been running an electronic records management system for over 15 years (first in Lotus Notes, then Documentum), which applied their corporate filing plan and retention rules to records. They had got an integration between e-mail and the electronic records management system, and a route for colleagues to save documents needed as a record from SharePoint into the electronic records management system.

At one point in the talk they gave figures for the total amount of storage taken up by the different information systems in their organisation. The electronic records system, with its retention controls, accounted for only 4% of the total storage. A further 33% were taken up by other document storage applications (SharePoint, shared drives, line of business systems, their website and intranet.) An astonishing 63% of the storage was taken up by e-mail – 47% in e-mail accounts and 16% in their e-mail archive.

I spoke to the archivist of the institution and asked whether she was concerned that only 4% of the records of the institution were under the protection and control of their retention schedule and fileplan. She said was indeed concerned, but she also pointed out in the days before e-mail, a national archive would typically only take between 3 and 5% of the records of government bodies- a similar figure to the percentage of documentation kept in that institution’s electronic records management system.

It was a good point, but there is an important difference. In the paper days a well organised central government department/ federal agency would have retention schedules covering almost all of their records, all across the organisation. The 3 or 5% of the records selected for permanent preservation in the relevant national archive was a distillation of the whole: like a capstone at the top of the pyramid of the organisation’s records.

In contrast the electronic records management approach leaves us with a situation where the vast majority of records (96% in the case of the institution referred to above) are outside of any retention control.

From an archivist’s point of view that would only be acceptable if the electronic records management system was routinely capturing the most important of the institution’s documentation.

But the (roughly) 5% of information/documentation captured by electronic records management systems is not necessarily the most significant 5% of documentation for the organisation.

An electronic records management system will typically contain a records classification that covers all of the work of the institution/organisation. Within that classification there will probably be a file (or a document library if their records system is built in SharePoint) for each significant piece of work undertaken by the organisation.

The problem is that these files will not be complete. There will be swathes of correspondence arising from those pieces of work that never make their way onto the relevant file/document library.

This is because filing routines are not consistent – they vary with the motivation, workload and awareness of each individual member of staff. This inconsistency leads to gaps in the files held in electronic records management systems. The files are set up to tell ‘the whole story of a piece of work’, but they rarely do.

On a day to day basis individuals rely on their e-mail account rather than the relevant file in the electronic records management system, so they tend not to act to fill in gaps in the file (and may not even notice the gaps).

In launching the Capstone consultation NARA are, in effect, saying that they do not trust the electronic records management system/SharePoint implementations of Federal Agencies to act as the capstone on top of the pyramid of all documentation and correspondence.

For the world of e-mail they are asking for a separate capstone – the e-mail accounts of senior staff.

NARA has no real option but to ask US Federal agencies to preserve the e-mail accounts of senior figures. NARA has a duty to future generations to preserve the correspondence of people playing significant roles in federal agencies. If such correspondence is not finding its way into the ‘official’ electronic records systems of those agencies then NARA needs those e-mail accounts.

Notes

- For an insightful discussion on the Capstone proposal read Barclay T.Blair’s blogpost of June 21 2013

- The latest update on Capstone I could find at the time of writing was this news piece from FCW published 21 August 2013

- The FCW news piece states that NARA will say more about Capstone at this event NARA are running for the vendor community on the 10 September. At the event NARA will issue ‘a grand challenge to industry’ regarding the type of technology needed with a view to ‘supporting Federal agencies as they implement the Managing Government Records Directive, particularly directive Goal A3.1.’ Goal A3.1 is the commitment ‘to work with private industry and other stakeholders to produce economically viable automated records management solutions’. @adravan pointed out to me on Twitter that the event will be discussing not just Capstone but electronic recordkeeping challenges in general.

An approach to archiving e-mails that makes them manageable, shareable, findable and useful (case study from the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations)

The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations (UN), with its HQ in Rome, exists to ‘spearhead international efforts to defeat hunger and build a food-secure world for present and future generations’.

Last week I recorded a podcast with Ian Meldon, a records management consultant working for the FAO, in which Ian described the approach of FAO to implementing a records management system based around e-mail.

FAO have had a system for managing electronic records for over a decade, and the system has always been based on e-mail. They recently replaced their old system with a new approach. The new approach involves:

- filtering out personal and trivial messages, so that significant messages can be managed and shared

- providing colleagues with ways of keeping abreast of the work e-mail traffic of team-mates, without those team mates having to copy each other into those e-mails.

- applying a records classification to significant e-mail messages without asking colleagues to interact with that corporate records classification

The previous records management system at FAO

From the year 2000 FAO had asked colleagues to copy or forward any e-mail needed as a record to the e-mail address of their local registry, where registry staff would file the e-mail in a Microsoft Outlook shared folder structure. The system worked tolerably well, although compliance with the policy varied from area to area.

One weakness of the previous system was that all the records were kept within the Microsoft Exchange environment. People could only see the records of their local area – there was no possibility of a FAO wide search. There was no sustainable way of holding and applying retention rules to the records.

Principles behind FAO’s new records management system

When FAO decided to overhaul the records system they based their approach on three principles:

- Don’t appear to introduce a yet another computer system FAO have procured and implemented a robust electronic records management system (Filenet from IBM), for use as their repository. But end-users never need interact directly with the Filenet repository – everything they need to do on the system can be done through the Outlook e-mail client.

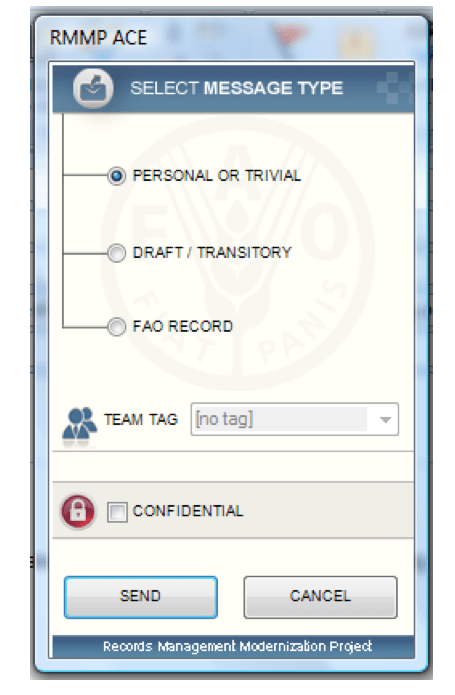

- Don’t ask people to do something they are not already doing The idea was not to ask users to do anything more time consuming than the previous system’s demand that they copy in the registry to significant e-mails. Under the new system every time a colleague sends an e-mail, a records capture pop-up appears asking them to say whether the e-mail is either a) personal or trivial or b) draft/transitory or c) FAO record. If an individual selects personal or trivial then the e-mail is sent without going into the records repository. If the individual selects either draft/transitory or FAO record then they are asked to choose the appropriate ‘team tag’ for the message (the team tag denotes which team they were working for in sending the message). The message then gets sent and a copy is placed in the records repository. There is also the opportunity to mark a message as confidential if it is work related but there is a need to restrict access to it.

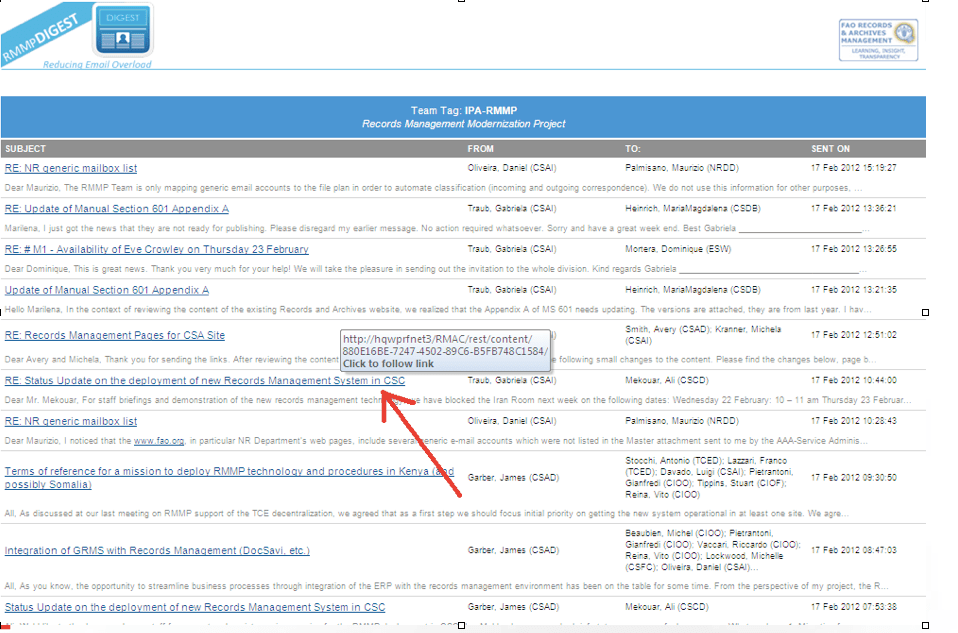

- Provide something useful beyond the need to keep records At 10pm every night the system generates a ‘digest’ for each team tag. The digest is an e-mail that lists and links to all the FAO Record e-mails sent that day and tagged with that team tag. This means that each morning an individual can see at a glance all the significant e-mails sent by colleagues in their team the previous day. This has reduced the need for colleagues to ‘copy each other in’ to e-mails. Furthermore individuals can choose to receive digests from other teams (if they have appropriate permissions). If a manager oversees six or seven teams they can look at the digest for the six or seven team tags each morning, without needing to be copied into hundreds of e-mails.

The illustration above shows the team tag digest e-mail generated by the records system for the team tag ‘IPA-RMMP (the Records Management Modernisation Project) on 17 February 2012. Members of the team, plus anyone who had decided to subscribe to that team tag, would have received that digest late on the 17 February. It gives them the subject line and first line of each e-mail. It is presented in reverse-chronological order by time sent. The digest is simply an automatically generated search query. Any colleague can search the records repository from their Outlook client and generate a similar report, showing the FAO Record e-mails of any team over any time period, provided only that they have appropriate permissions for that team tag.

The nature of the team tags

FAO created team tags by simply asking every area of the organisation to identify what teams they had, and who worked in those teams.

Team tags are maintained by registry/records management staff who create new team tags when new teams or project teams emerge, assign individuals to membership of particular team tags, and maintain the access permissions around team tags.

An individual might belong to one, two or several teams. When they send an e-mail from the Outlook client the records capture pop-up asks them to assign a team tag to it if they have marked it as draft/transitory or FAO record.

The pop-up presents them with a drop-down list of the teams they are assigned to. If the individual is assigned to only one team then they have no choice to make – the team tag will be filled in automatically.

Application of the record classification

FAO created a records classification based on a functional analysis of the activities of their organisation.

The challenge was how to apply the records classification to the records that would build up in the system. If FAO had asked individual users to place each e-mail into a file within that records classification then it would have broken their principle of not asking people to do something they were not already doing (in FAO’s previous system registry staff had placed e-mails on files on behalf of end-users).

Experiments with auto-classification

The first approach FAO trialled was auto-classifcation, where an auto-classification tool would allocate e-mails declared as Draft/transitory and FAO Record to the appropriate functional classification.

Daniel Oliveira who worked on the project with Ian, told me that the auto classification worked amazingly well in areas such as the finance where the subject of messages were relatively consistent and predictable, but it did not work nearly as well in the policy areas where the subjects of messages were unpredictable and unrepeated. Policy work constitutes a significant proportion of FAO’s work.

Mapping team tags into the functional records classification

The approach they settled on was simply to map the team tags into the functional records classification. Each team tag is linked to one node in the records classification.

FAO are building up in their repository what is in effect a correspondence record for each team, sortable by sender, recipient and date. Each of these correspondence records is linked to the functional records classification, from which it can inherit a retention rule.

To my eyes they have struck a neat balance between the strongly individual centric nature of e-mail as it has emerged over the past two decades, and the more collective tradition of files and record keeping.

Access permissions on e-mail

E-mail saved as ‘draft/transitory‘ and ‘FAO Record‘ enters the records repository (FileNet) and inherits its access permission from the team tag, unless it had also been marked as Confidential. FAO encourages teams wherever possible/appropriate to authorise all FAO staff to access the e-mails tagged with their team tag.

Teams are able to set a different access permission for ”draft/transitory‘ than for ‘FAO Record‘ if they wish to make a distinction.

How FAO deals with incoming e-mail

When FAO colleagues go to send an e-mail, a records capture pop-up intervenes to prompt them to capture the e-mail to the records repository if it has some significance.

However when colleagues receive an e-mail there is no such opportunity to intervene with a pop-up.

FAO provide staff with two alternative ways of capturing incoming e-mails as records:

- Treating an incoming e-mail in the same way as any reply made to it – when a colleague goes to send a reply to the e-mail the records capture pop-up intervenes – if they indicate that the reply is FAO Record (or draft/transitory) then not only the reply, but also the incoming e-mail that prompted it, will be captured into the repository

- Right click menu option – colleagues can select a message in their inbox and use the right click menu to capture it into the record repository and give it a team tag

How FAO deal with e-mail sent from mobile devices

There is a trend for colleagues to access e-mail via mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets. These devices do not have the extended Outlook client with the FAO records capture pop up. There are too many varieties of smartphones/tablets out there for it be feasible for FAO to develop a customised e-mail client for each device.

FAO have given staff a generic e-mail address that they can copy e-mails sent from their mobile devices into. Staff working in the Registries capture those e-mails into the system and give them the appropriate team tag.

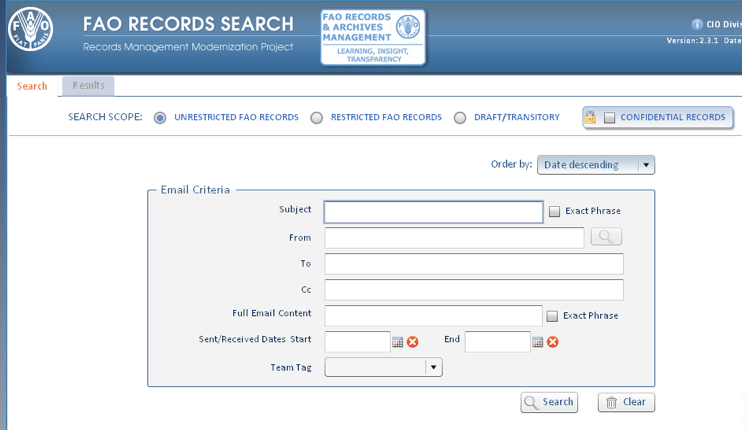

Searching for e-mail

The search facility for the records system is built into the Outlook e-mail client.

To my eyes the search looks more intuitive than the advanced search in a typical electronic records management system. This is because the metadata of e-mail (from/to/cc/subject/date) is simpler, more standardised and more intuitive than the metadata collected from end users in document profiles by electronic management systems.

This search allows people to specify a date range they are interested in, and to generate what is in effect a report of all the working e-mail sent/received by a particular individual or team within that date range (assuming they are in the appropriate permissions group)

Conclusions

There are six aspects to the FAO approach that I find particularly valuable and interesting:

- They haven’t tried to fight e-mail they have not tried to get users to move e-mail out of the e-mail environment and into an environment that works on a completely different logic (the logic of a folder structure/ fileplan hierarchy)

- They have used the strengths of e-mail – the fact that you can intuitively search and/or sort e-mail by sender/date/recipient and title; the fact that you have the context of who a document/messages was communicated to and when; the fact that colleagues spend most of their computer time in the e-mail environment; the fact that any document of any significance in environments such as the shared drive will pass through e-mail

- They have mitigated the main weakness of e-mail – the fact that trivial and personal messages sit cheek-by-jowl with work messages and make it problematic to provide access to the e-mail of colleagues

- They have paid as much attention into making sure that the records function as a useful information and news source for colleagues, as they have paid to making sure people contribute records to the system

- Their approach does not depend on any particular proprietary software. They have used a proprietary electronic records management system as their repository for the e-mail, but they could have used any one of a number of different electronic records management systems and achieved similar results. The customisation of the e-mail environment was done by their in-house development team. Their approach does not depend on clever algorithms or sophisticated auto-classification rule engines.

- They have moved away from files and filing, but still group records into meaningful and manageable aggregations Records are accumulating in manageable aggregations, but these aggregations are slightly different from files we have been used to in old paper filing systems, and the files that we created in electronic document and records management systems. Those files attempted to capture the whole story of each particular piece of work. They depended on teams setting up a new file for every new piece of work that they started. The nearest equivalent of the file in the FAO set up is the team tag. But teams have not been required to create/request a new team tag every time they start a new piece of work – they keep the same team tag for all the work they undertake. The record is in effect a correspondence record of that particular team over a particular time. This is less granular than a traditional file structure. But the loss of granularity is compensated for by the ability to sort on sender/recipient and date.

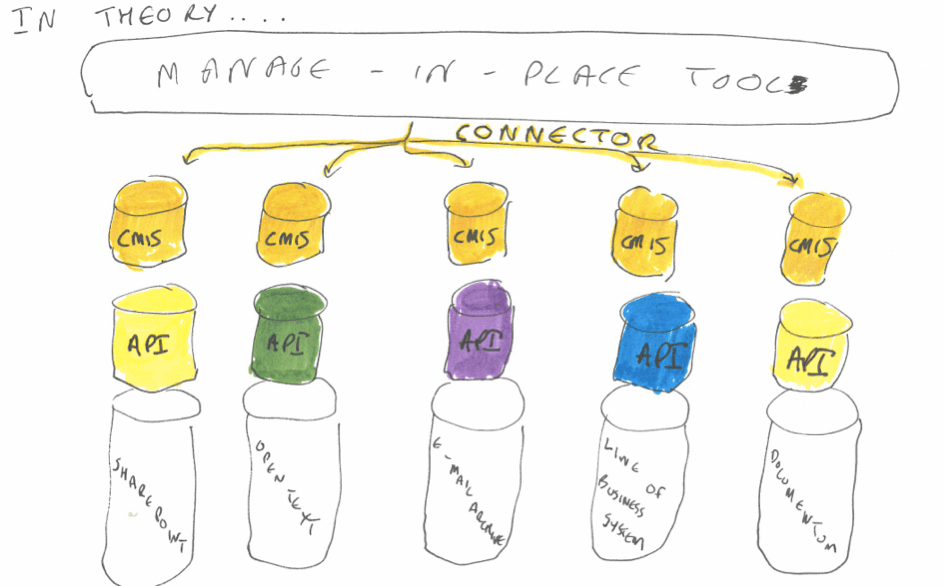

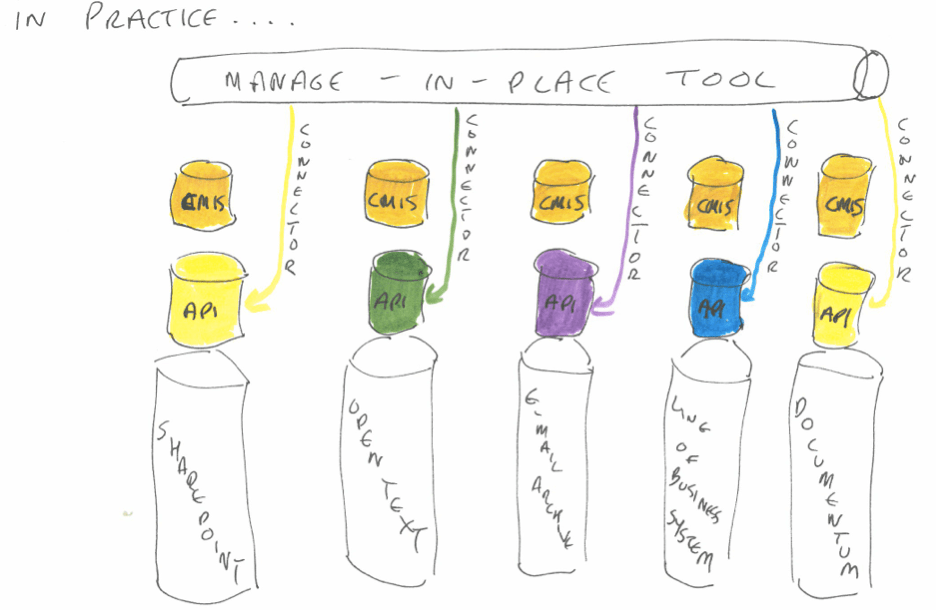

The mechanics of manage-in-place records management tools

At the IRMS conference in Brighton in May I had conversations with several vendors of manage-in-place records management tools about how they went about ensuring that their products could connect with the applications in day-to-day use within organisations

The importance of APIs (application programming interfaces)

In order for the manage-in-place tool to work it needs to have a ‘connector’ to each content repository that it wishes to govern.

The connectors are typically built to use the API (application programming interface) of the content repository. The API exposes a subset of the content repository’s functionality. It specifies how any authorised external application (in this case a manage-in-place tool) can issue commands to the content repository.

Some of the things that a records manager might want their manage-in-place tool to do inside the various content repositories of your organisation include:

- adding metadata to a document or aggregation of documents

- linking an aggregation of documents to a node in a records classification

- preventing editing or deletion of a document or aggregations of documents

- linking a retention rule to a piece of content or an aggregation of content

The beauty of the concept of an API is that the two applications can interact with each other without you having to customise either application. It does not matter if the two applications are written in entirely different programming languages. Nor does it matter if one or both of the applications are based in the cloud.

In theory:

- you could replace your manage-in-place tool with a new manage-in-place tool from a different vendor, and none of the content repositories need notice any difference (provided that the new manage-in-place tool carried on issuing the same commands to their API)

- you could replace a content repository with a successor repository from a different vendor without the manage-in-place tool noticing any difference (provided that the new content repository offered a similar API that enabled them to make the same commands)

In practice each vendor constructs the API for their content repository differently, and this creates two challenges for the makers of manage-in-place tools

1) they have to construct a different connector for each different vendor’s content repository. Two of the manage-in-place providers I spoke to at the conference (RSD and IBM) both provided connectors to over 50 different commonly used content repositories.

2) some APIs are better than others. Some applications expose more functionality through their API than other applications, and hence let the manage-in-place tool do more things to their content. One example cited was that the manage-in-place tool can get some document management systems to display the organisation’s records classification (fileplan), so that users of the document management system can link or drag and drop content to the appropriate node in the classification. Other document management system do not have that functionality exposed in their API.

CMIS (Content management interoperability services)

CMIS is a specification that aims to overcome the first of these two problems. The specification was drawn up by a coalition of vendors in the ECM space under the auspices of the OASIS Technical committee.

The idea is that vendors add a CMIS layer to their applications. Just like an API, the CMIS layer exposes a subset of the functionality of the native application, so that an external application can make use of that functionality. The difference is that whereas each vendor’s API is constructed and expressed in a different way, a CMIS layer is standardised. This means that a similar function (for example ‘add a document’) would be expressed in the same way in the CMIS layer of each vendor’s products.

A mange-in-place tool vendor could choose to build connectors to the CMIS layers of content repositories, rather than through the API. In theory this saves a manage-in-place vendor from building seperate connectors for every different type of content repository they want their product to be able to govern.

In practice the vendors of the manage-in-place tools that I spoke to told me that they prefer to write connectors that use the API of each application, rather than the CMIS layer. This is simply because most repositories expose more functionality through their API than through their CMIS layer.

CMIS and records management

The disadvantage of CMIS being writtten by vendors is that a coalition of vendors have to agree for functionality to be put into the specification. They have tried to capture concepts and functions that are common to all or most existing repositories. Functionality such as records management, which some repositories have and some don’t, has not received prominent treatment in CMIS. The first version of CMIS had concepts such as a document, and a folder, but it did not support retention rules, nor a records classification/fileplan (although it did have the concept of a folder structure).

The latest version of CMIS (1.1) does have retention functionality in for the first time. But that has not pleased all of the vendors. Jeff Potts, of Alfresco wrote this in his blogpost announcing the approval of CMIS 1.1

This new feature allows you to set retention periods for a piece of content or place a legal hold on content through the CMIS 1.1 API. This is useful in compliance solutions like Records Management (RM). Honestly, I am not a big fan of this feature. It seems too specific to a particular domain (RM) and I think CMIS should be more general. If you are going to start adding RM features into the spec, why not add Web Content Management (WCM) features as well? And Digital Asset Management (DAM) and so on? I’m sure it is useful, I just don’t think it belongs in the spec.

This is the dilemma for CMIS:

- if they do not give full coverage of sets of functionality such as records management then manage-in-place tools will bypass the layer and just use the APIs of the content repositories.

- the more detailed and precise their definition of records management functionality is, the harder it is to get the coalition of vendors to agree on it

From a records mangaement point of view what we want out of CMIS (or any other standard in the API space) is to set out a minimum set of records management functionality that the API of every business systems sbould have.

In theory, if CMIS specified a set of API commands that would expose the functionality needed by one or more of the current electronic records management specifications, then vendors would never have to re-architect their product to meet that electronic records management specification, All they would need to do is expose the relevant functionality in their CMIS layers and let the manage-in-place tools use that functionality to govern the content they hold.

Of course this would not solve all of our problems – one of the biggest content repositories in most organisations are simple shared network drives, that don’t have an API (never mind a CMIS layer!).

Electronic files that tell the whole story of pieces of work – will we ever get there?

Here is a quote from one of the respondants to the recent survey by State Records New South Wales of e-mail usage in public authorities

Even when emails are captured in our EDRMS (electronic documents and records management system) users focus on capturing emails from their inbox (i.e. email received) and forget about the need to capture sent emails. While it is easy to set up automated links between email folders and the EDRMS, a set and forget method, users fail to save their sent emails to the linked folder. I have failed to find an elegant, non-intrusive method to achieve the capture of the whole ‘story’.

The vision of having colleagues co-operate together to maintain a file that tells the whole story of a piece of work remains tantalisingly out of reach, even in the case of the organisation quoted above, who seem to have done all the right things.

They have integrated their electronic records management system with the e-mail client so that folders in staff e-mail accounts can be linked to folders in the records system. What more can they do?

The market will bring a solution to the specific ‘sent items’ problem that the respondent mentioned,through some sort of conversation threading so that sent e-mails are treated together with the e-mails that they responded to/received in response.

But at the same time it will bring different disruptive technologies – for example-mail access on smart phones that are too small to support drag and drop to folders; cloud e-mail that might prompt an organisation to dispense with the e-mail client that had been integrated to the electronic records system etc.

Technology gives with one hand and takes with the other. And the sheer fact of constant change means that colleagues/end-users do not have enough time in any one technological configuration to develop the shared routines and habits that would lead to them keeping a complete electronic file for each piece of work that their team undertakes.