One of the founding principles of archival science is that the original order of records should be respected. If an organisation was to retrospectively restructure a set of records, in a way that obscured or lost the original order, then this would risk giving a misleading picture of:

- how content had accumulated

- how people had worked

- who had known what, when, in relation to the work that the records arose from

One of the great strengths of digital (as opposed to analogue) records is that they can be presented or viewed in so many different ways and orders. Does the principle of respect for the original order of records still hold true in the digital age? Is a digital repository likely to have one structure that will tend to act as the best vehicle for the application of retention rules, the taking of disposition actions and the making of appraisal decisions on content within the repository? We can use a simple thought experiment to show that the principle does indeed still hold true.

Thought experiment to show the original order of digital records

Imagine you are a records or information manager, reviewing a legacy digital repository (think of a legacy shared drive (fileshare), or a legacy SharePoint system, or a legacy email system). You could reorder that repository in an unlimited number of ways, at the press of a button, with a few lines of code, or with a well-engineered prompt.

Now travel back in time a little and imagine yourself in the position of an end-user who is using a shared drive, a SharePoint site, an email account or in the course of their work. They would have been able to re-order content within that particular shared drive, that particular SharePoint site, or that particular email account. But it is unlikely that they would have been able to re-order content across the entire repository of shared drives, the entire repository of SharePoint sites or the entire repository of email accounts.

In corporate systems such as shared drives, SharePoint systems, email systems and the like, end-users are given partial access to the system. They can contribute to one or more containers within the system, but not to the rest. They can access one or more containers in the system, but not the rest.

This partitioning of the system is necessary in any all-purpose system that can be used by all or most of an organisation’s staff to conduct all or most of their business activities. It is necessary because in a large organisation with a sophisticated division of labour, it is not normally advisable to allow individuals to be able to view, edit and contribute content in all parts of the system.

The importance of containers within digital repositories

The order that has the most influence on how content accumulates in a digital system is the order which determines who can contribute content where, and the order that sets default access permissions on content. To find the original order we therefore have to find the groupings on which default access permissions were set within the system. This order also strongly influences how people behave in a system. People are likely to alter their communication style, and alter the types of information they are willing to share, depending on the access permissions of the particular container they are contributing to.

Content in corporate digital systems tends to be partitioned into containers within which a defined individual, team or work group can contribute content:

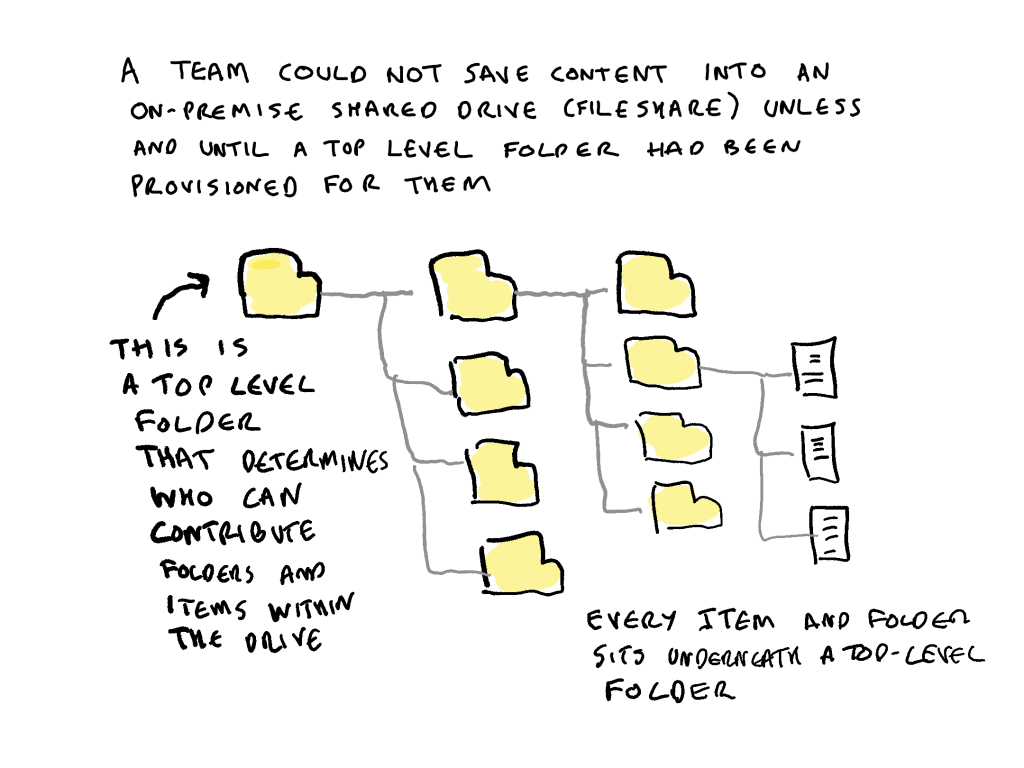

- in the on-premise world before the coming of cloud suites, a teams could not work in shared drives (fileshares) until someone had provisioned them a top level folder

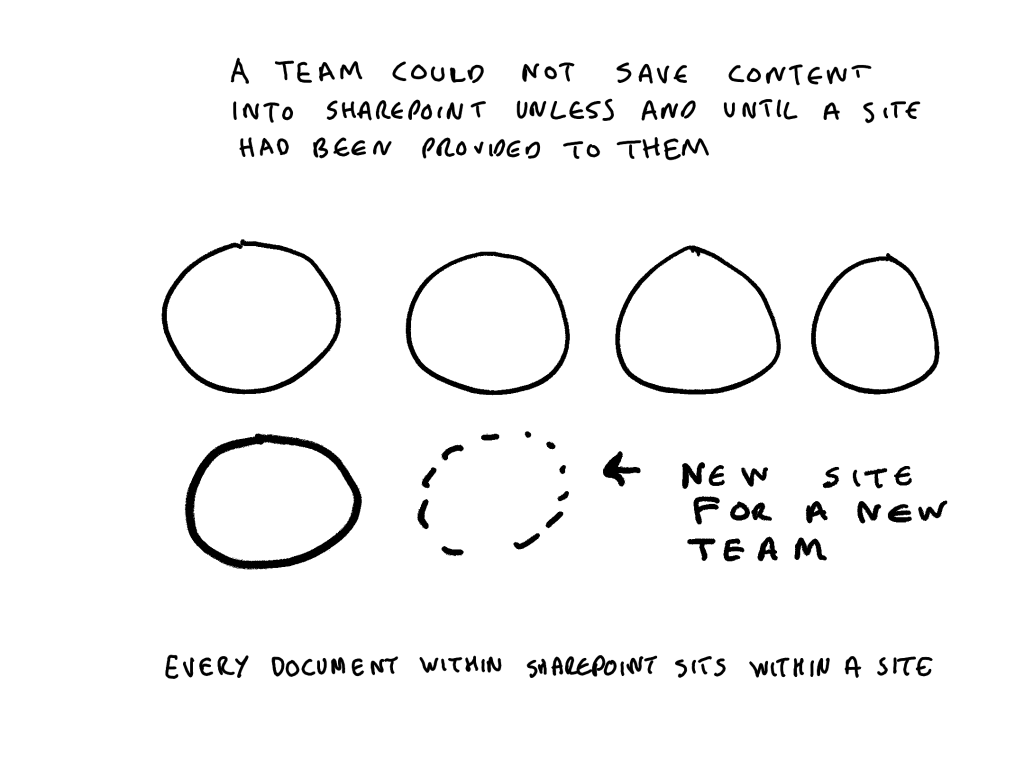

- a team cannot work in SharePoint until someone has provisioned them a SharePoint site

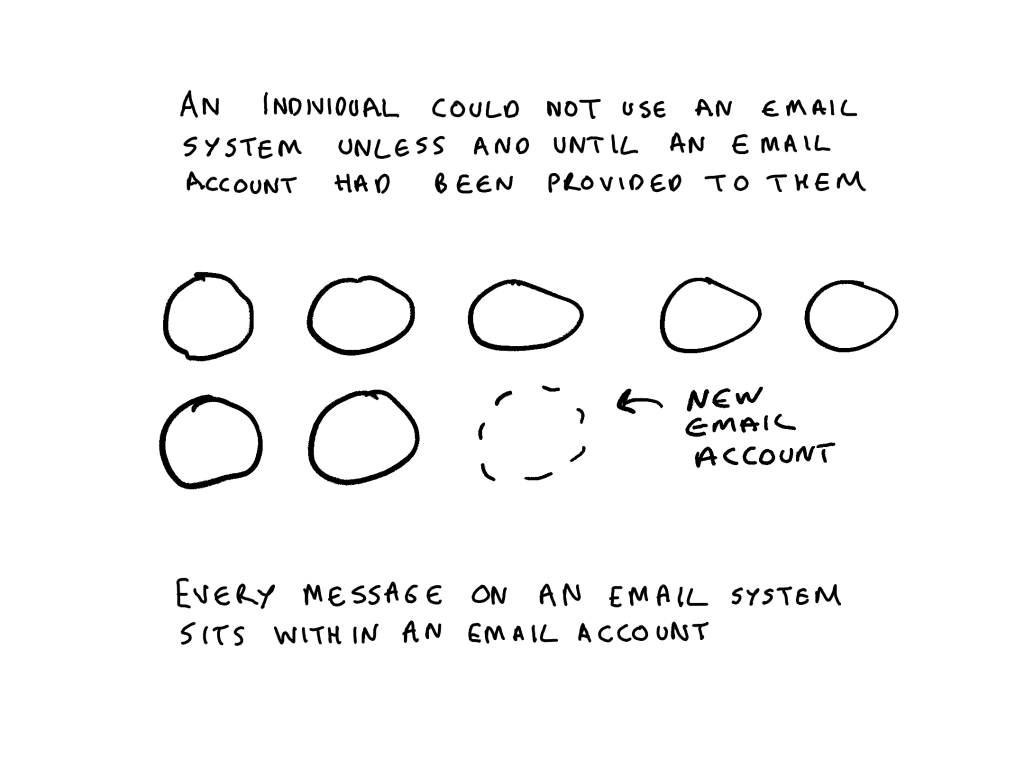

- an individual cannot work in an email system until someone has provisioned them an email account that they can use

Every item within a corporate all-purpose digital system has to have an access permission attached to it from the first moment that it is saved into a system. Therefore there needs to be some way of applying default access permissions to all content. Containers are the vehicle through which default permissions are applied. Every item therefore must sit within a container.

In a SharePoint system every document sits within a site. In an email system every message sits within an email account. In a on-premise shared drives every item sits underneath a top level folder. In Microsoft 365 , MS Teams uses SharePoint, OneDrive and Exchange as its repositories. Every document, post or message contributed to a Teams channel or chat conversation is stored in either a SharePoint site, a OneDrive site or an Exchange email account.

This means that if a records/information manager has a means of acting on containers then they have a means of acting on all items within the repository. This makes containers a very powerful way of controling content in live digital repositories, and of scaling up actions and decisions on content in legacy digital repositories.

The intuition behind this post

This is the second in a series of posts that attempt to articulate intuitions about records management for data scientists. The intuition behind this post is as follows:

Corporate all purpose digital systems are systems that can be used by all or most members of staff to work on all or most of their activities. Examples include email systems, collaboration systems, shared drives (fileshares) etc.

Content in such systems tends to be partitioned into containers within which a defined individual, team or work group can contribute content. All items within the repository will have been contributed to one of those containers.

The previous post in this series is Intuitions about records management for data scientists

(all views in this post are my own)